Your cart is currently empty!

White City London: After the exhibitions

The White City London exhibitions have been well covered elsewhere, but the site’s history after the exhibitions ended remains less explored. Let’s delve into what became of this iconic location.

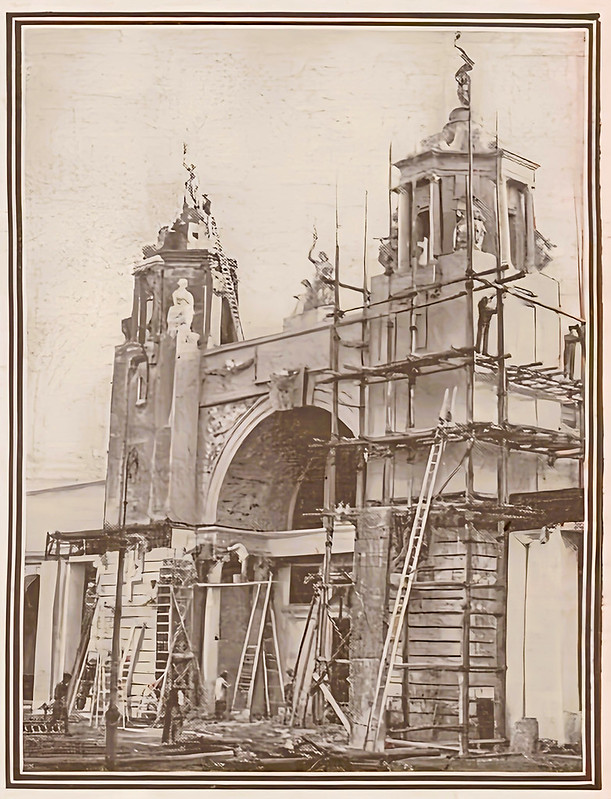

The site was named after the first exhibition held there, the Franco-British Exhibition of 1908. Imre Kiralfy was the man responsible for designing and constructing the £900,000 project The exhibition featured 20 pavilions showcasing various aspects of culture and industry, along with 120 smaller buildings, half a mile of artificial waterways, an amusement park, and extensive tree-lined walkways—all completed in just 16 months. Most of the buildings were finished with white plaster, which inspired the name “White City.”

From the outset, the site was designed not just for a single event but as a venue capable of hosting multiple exhibitions over the years.

The site also included a large stadium with a capacity of 100,000 people. The 1908 Olympic Games were due to be hosted in Rome but Mount Vesuvius erupted and messed everything up. White City was drafted in as a last minute replacement.

That year marked the establishment of the modern marathon distance. The race began at Windsor Castle and stretched to the finish line at White City, covering a distance of 26 miles and 385 yards. This has since become the standard marathon distance still used today.

List of exhibitions:

1908 – Franco British Exhibition.

1909 – Imperial International Exhibition

1910 – Anglo Japanese Exhibition

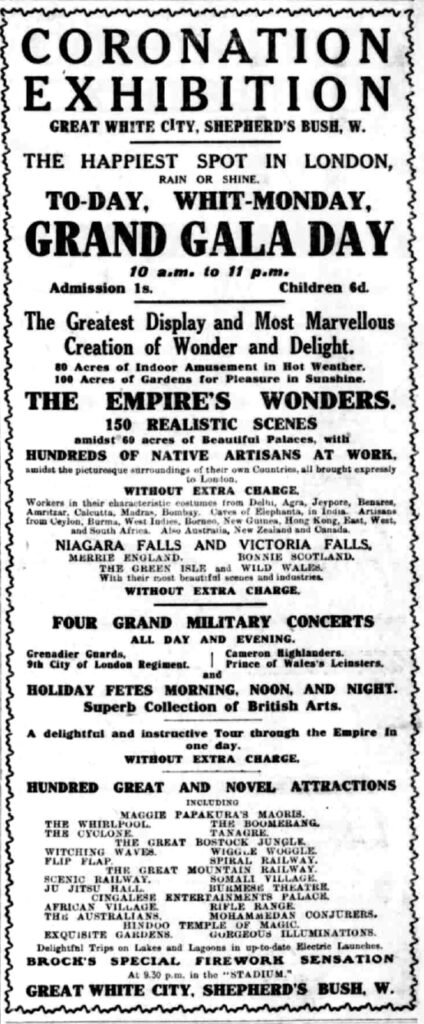

1911 – Coronation Exhibition

1912 – Anglo Latin Exhibition

1914 – Anglo American Exhibition

The site got off to a great start, hosting a major exhibition every year from 1908 to 1912. Most were highly profitable for all concerned. A lot of the same buildings were reused from year to year, sometimes re-themed or modified in some way. Smaller rides and attractions came and went. The larger amusement rides were retained from year to year and featured names such as the Flip Flap, Wiggle Woggle, Witching Waves and Roly Poly. A 1908 newspaper report stated that “visitors are clearly more interested in the Flip Flap and Scenic Railway than in the English and French art, and the industries represented”

Around this time two other large London exhibitions were held: The 1909 Golden West & American exhibition (Earl’s Court) and the 1911 Festival of Empire exhibition (Crystal Palalce) which attracted 5 million visitors.

White City remained closed in 1913 but was refurbished for the Anglo American Exhibition in 1914. Most of the buildings were repainted “salmon-pink and cream” with some referring to it as ‘Pink City’.

Word War I – The glory days come to an end

In October 1914, following the outbreak of the First World War, the White City site was requisitioned for military use. Within a month, 10,000 soldiers had taken up residence, with bomb shelters quickly dug across the grounds. The Flip-Flap ride was fitted with massive searchlights to serve as a navigational aid for airships approaching Wormwood Scrubs. Existing buildings were transformed into factories and warehouses, and the site became a bustling hub of wartime production. At its peak, it employed 20,000 people, earning the distinction of being the largest factory site in the world.

By November 1915 a tent-making factory was churning out 5,000 bell tents every week. They also made hospital marquees, canvas bags, nose bags and even gas masks for horses. Other buildings were used to make ammunition and clothing, Many of these factories, along with others making airplane parts, were owned and operated by furniture company Waring & Gillow who made a “very considerable fortune” producing equipment under government contracts. It was said that 75% of the tents used during the war were either made in White City or passed through the site.

Another factory built over 2,000 airships, a fact that only came to light after the conflict was over. The big stadium was used for storing millions of wooden packing cases “The cases were stacked as high as houses, the effect being that of a miniature city formed of shell cases, with narrow streets running between the “houses” and hundreds of lorries and other vehicles, passing up and down the narrow avenues”.

Because of the large percentage of female workers, lots of shops had sprung up around the perimeter of the site selling “all kinds of things that appeal to a woman’s eye”.

The site is handed back..

Most of the complex was handed back in Feb 1920 and a reporter for The Globe newspaper toured the site:

“The White City is no longer the city of gleaming palaces, but a scene of grey ruin, calling to mind some shell-shattered town in Flanders. The famous Court of Honour, in which a multi-coloured waterfall descended into the illuminated lake, is a gaunt skeleton of its former beautiful self. The lake is drained and full of rubbish. Bare rafters protrude through many the domes and minarets. All the elaborate ornamentation of the surrounding courts, with their lattice-work harem windows, has suffered severely. The parapets of the bridges have been demolished, the debris lying in the emptied lagoon. Doorways of several buildings have been battered by lorries when they backed up for their loads. What was formerly the popular Mountain Railway resembles in the distance some mammoth ruin of old Rome. The extensive grounds which were at one time the pride of the Exhibition are overgrown with rank grass and ivy. The Japanese Garden, which was laid out by the Royal gardeners from Japan, is marked only by the surviving picturesque tea chalet, which stands amidst a scene of desolation, where nature has run riot. Great heaps of rubbish from the adjacent Courts have been cast into the cavity that formed the lake”.

The site owners submitted a claim for £1 million as compensation for loss of business, and damages sustained during the occupation. A hearing took place at the War Losses Commission lasting several days. The government made every effort to deny liability and went over the claim with a fine-tooth comb. For instance, the owners wanted £4,030 to restore the Japanese Garden. However, the Solicitor General argued that by 1914, the garden was already in a “very neglected condition” and questioned why the government should be responsible for restoring it to its former glory.

Ultimately, the owners were awarded a total of £358,000. Plans for an Inter-Allied Victory Exhibition were scrapped.

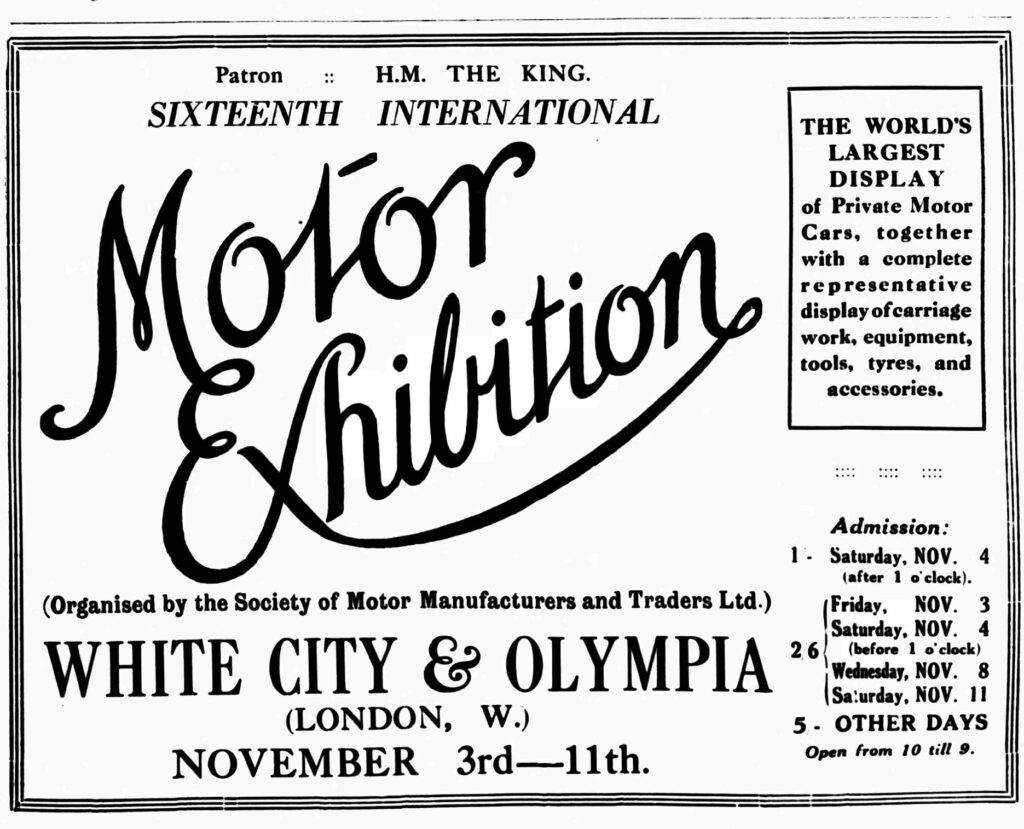

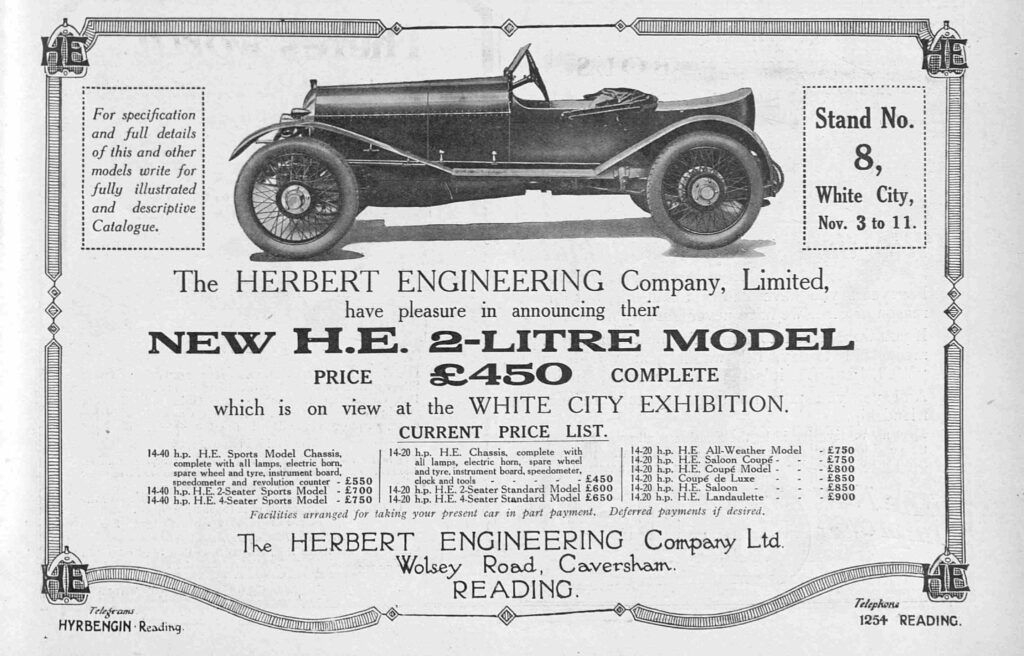

Due to limited space at Olympia, the 1920 Motor Show was shared with White City. A free bus service connected the two sites and the Metropolitan Railway reopened its Wood Lane (White City) station. The divided venue was universally unpopular although many visitors found the White City section to be cleaner, easier to navigate and less chaotic. But the White City exhibitors were far from happy and felt they were treated more like a “sideshow” to the main event at Olympia. The Moror Show continued to be divided between the two sites for the next two years, but in 1923 a new expansion opened at Olympia allowing the show to be held under one roof, spelling the end of White City.

In March 1922, the trade-only British Industries Fair was held at the site, soon establishing itself as the largest event of its kind globally. The fair continued at White City for the next 15 years, eventually growing so large that it expanded to include Olympia in London and Castle Bromwich near Birmingham. By its later years, the White City portion alone was drawing 100,000 visitors over its 10-day span, with evening hours opened to the public due to popular demand. The King and Queen made a point of attending each year. During the 1922 fair, the King was captivated by a new invention, the pogo stick, though he politely declined an offer to try it himself.

Around the same time, plans were announced for a new British Empire Exhibition to be held in 1924. But the government decided to locate it on a new site in Wembley, much to the horror of Wembley council, which opposed the idea. The derelict grounds at White City were deemed unsuitable, despite a local reporter guessing they could have refurbished it all at a quarter of the cost.

In the summer of 1922, a thousand ex-soldiers were hired to clean up the site and patch up the worst of the damage. The larger buildings were converted into eight new exhibition halls, providing 150,000 square feet of covered space. But much of the site was left untouched, including most of the smaller buildings and the amusement rides. These derelict structures became an eyesore for many years to come.

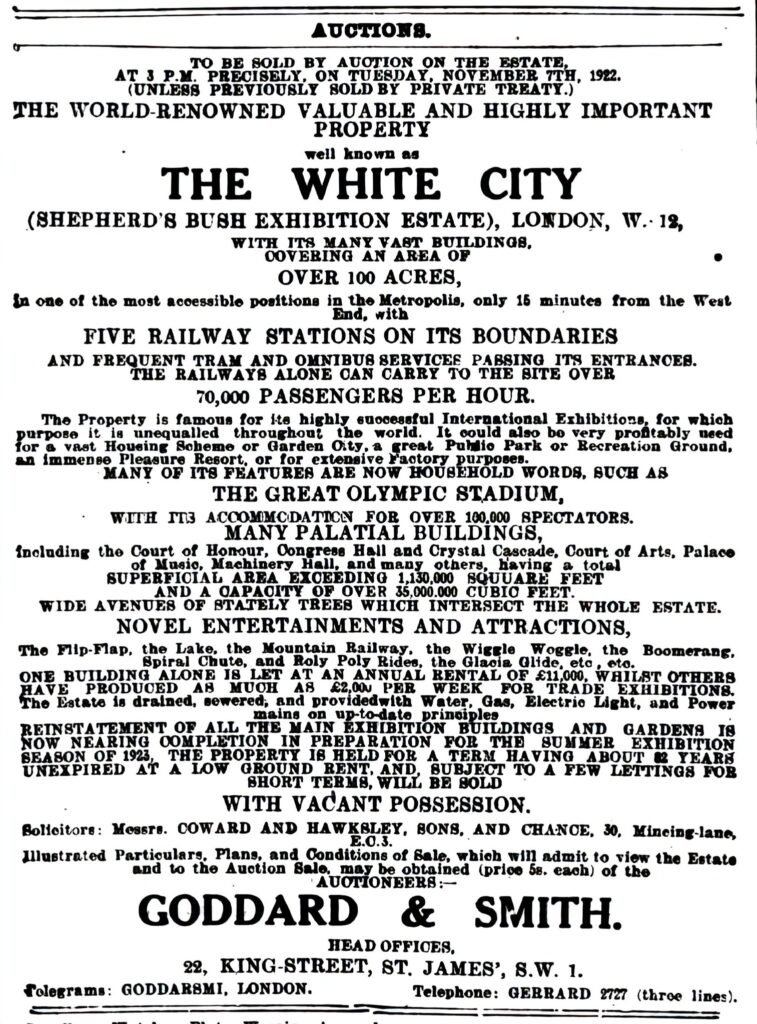

In November of that year, the site was put up for auction with a guide price of £750,000. Rumors circulated that an American syndicate was interested in purchasing the site to construct “huge blocks of apartment houses similar to those in New York.” However, these rumors proved false, and after an auction lasting less than a minute, the site was acquired by theatrical press agent Eustace Gray for £500,000. He was suspected of being the front man for a secretive syndicate, but Mr. Gray claimed that the purchase was purely a private venture, and that he intended to reopen it again for exhibitions.

He paid a deposit of £50,000 but later failed to provide the remaining funds, resulting in the cancellation of the deal. By December, the site was back on the market. Apparently the deposit was not refunded.

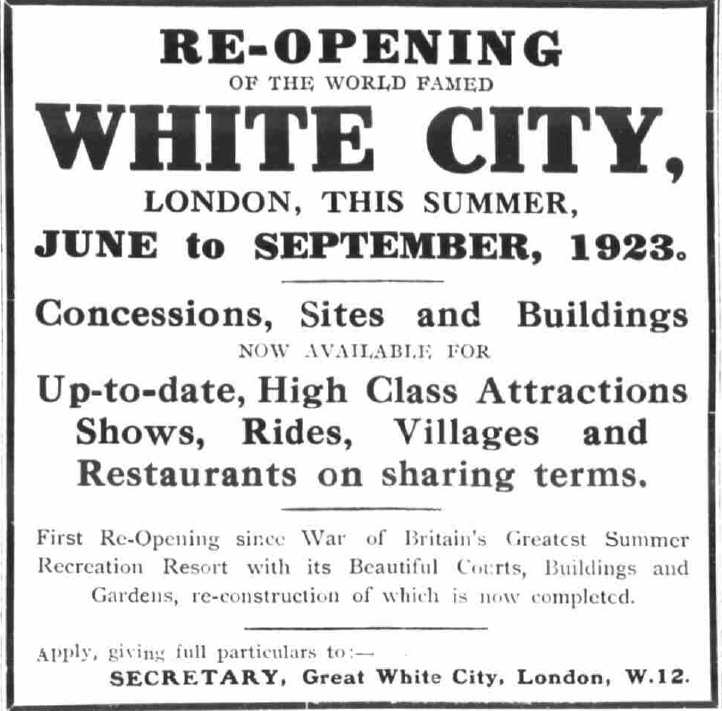

In June 1923 the site reopened to the public for three months, the idea being to turn it into an entertainment centre or pleasure ground. Most of the old amusement rides remained closed but a new 300ft high see-saw ride was built. But it was not a huge success and was not repeated the following year.

The site continued to be popular for smaller fairs and exhibitions as organisers liked the flexibility to rent one or several halls. Most of these events were “trade only” with one being described as “not lavishly advertised, it has no flip-flaps or wiggle woggles or other coaxers of the nimble sixpence”. Competition for trade shows was intense with both Olympia and Crystal Palace also fighting for business. Crystal Palace was not popular during the winter as it was almost impossible to heat.

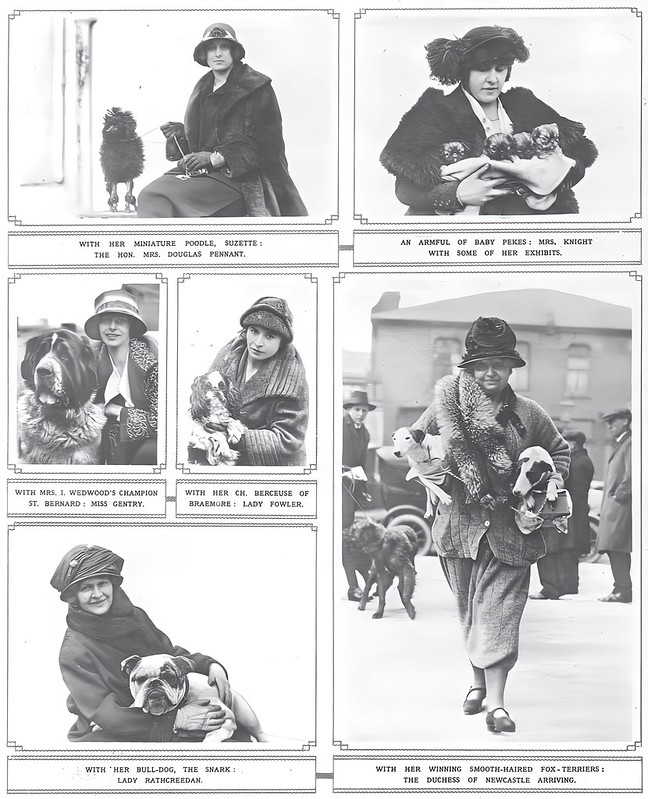

In 1924 the site began hosting the Kensington Canine Society’s annual dog show which featured the “heaviest dog in Great Britain”, a St Bernard which weighed over 14 stone. That same year it also hosted a large fashion show.

At the 1926 Industries fair, the King was horrified to learn that 24,000 typewriters used by the British government were of American manufacture. He said it was “scandalous” and vowed to investigate further. The matter was even raised in Parliament where it was stated that most had been bought during the war when homegrown typewriters were in short supply. Within a few weeks two major British typewriter manufacturers were inundated with orders, one said they had been “cleared out”, the other said it was having to take on more staff to cope with the rush of orders.

The stadium became a popular venue for athletes training for the 1924 Paris Olympics and also hosted regular Sunday orchestral concerts. But the new Wembley Stadium began to draw away much of the business.

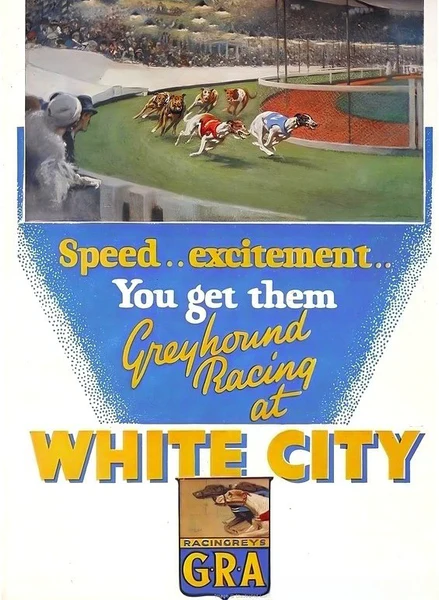

Greyhound racing “the popular American sport” was introduced at the stadium in 1927 by Brigadier-General Alfred Cecil Critchley who obtained a 99-year lease on the stadium. Critchley had introduced greyhound racing to Britain the previous year when he opened his first track at Belle Vue, Manchester. New kennels and training facilities were built in the shadow of the old Flip Flap ride, which was described at the time as “still there, lying rusty and prostrate.” This new greyhound area became known as Flip Flap Town and could accommodate up to 200 dogs, “some valued as much as £100 each”. The races attracted impressive crowds, regularly drawing between 25,000 and 40,000 people. The stadium was refurbished with a roof over all the seats. A new restaurant opened

In 1931 Queens Park Rangers football club relocated to the stadium as it offered better facilities for fans including undercover seating. But two years later, after losing 7,000, they moved back to their old Loftus Road ground saying that White City was just too big and expensive.

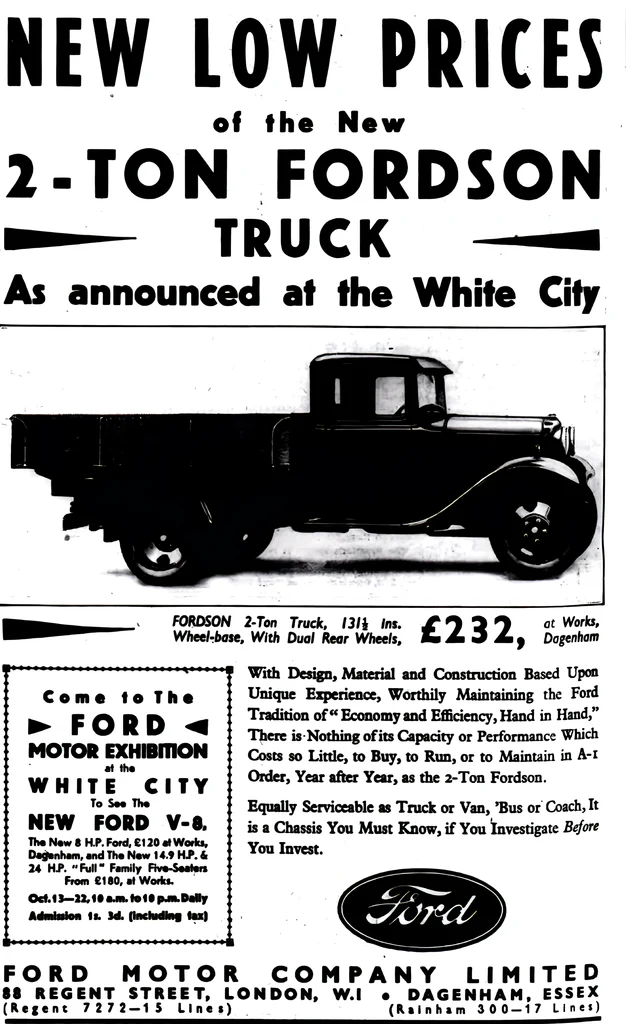

In 1932, in conjunction with the Motor Show at Olympia, the Ford Motor company held their own motor show at White City allowing for cars, tractors and commercial vehicles to be displayed and driven around the site.

By the mid-1930s the site was looking rundown again with one visitor remarking “they ought to do something about the dilapidated appearance. A close inspection shows the dirty white paint of the buildings to be peeling and outwardly the place resembles a derelict fun fair”. Another said the site consisted of “crazy ruins of faded and crumbling structures which survived so long they made a mockery of childhood memories”. It was common practice to cover the interior walls with large flags, canvas sheets and posters to cover up the holes and decay underneath.

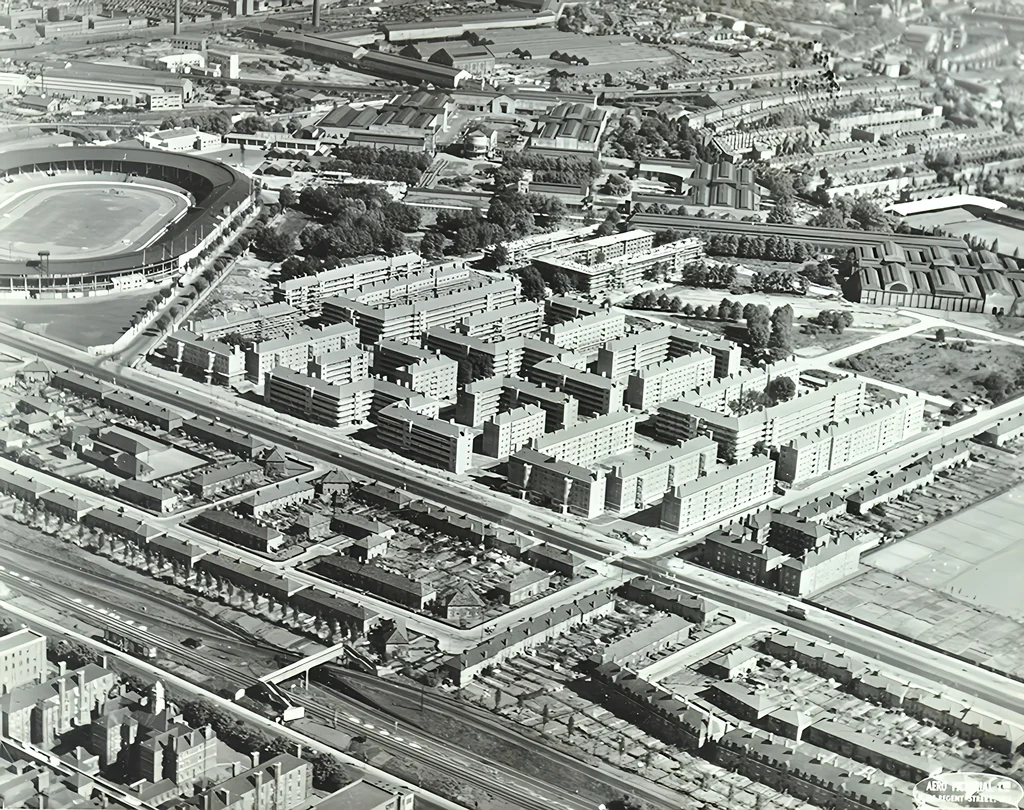

In 1936, the London County Council announced plans to compulsorily purchase half of the site and redevelop it into flats for 11,000 people, an idea first suggested back in 1928. Disputes arose over the level of compensation; the land owners claimed the site was worth £627,000, while the council offered only £298,000. An application to the High Court to quash the order was dismissed. Plans were soon drawn up for 2,166 flats in 49 five-storey blocks. It became the largest construction scheme for flats ever undertaken by the council. The stadium would remain unaffected.

The Industries Fair took place as usual in February 1937 with stand frontage at White City and Olympia now reaching a total of 14 miles—”one has to be quite energetic to visit it all.”

Several old derelict amusement rides, most unused since the 1914 exhibition, were sold to George Cohen and Co. for scrap in February 1937.

In August 1938, 2,000 workers moved in, and the first flats were ready a year later. Heating consisted of just one fireplace in the living room, and disputes soon arose after certain coalmen refused to carry the heavy bags up to the fifth floors, forcing residents to drag it up themselves. Frozen water pipes became another issue. Many residents rented electric heaters from the council to warm their bedrooms. After the war, gas fireplaces were installed with the option for tenants to add central heating, the cost of which would be borne with an increase in rent—most declined. Full-scale central heating did not begin until the mid-1970s, by which time the flats were being described by locals as a “sink estate”.

In 1939 the stadium at white city attracted a crowd of 80,000 for the world light heavyweight boxing championship.

The remaining 28 acres was requisitioned during World War 2, with the Territorial Army remaining on site afterwards. In 1947 the council announced they were compulsory purchasing the land, most of which was still covered with derelict exhibition buildings.

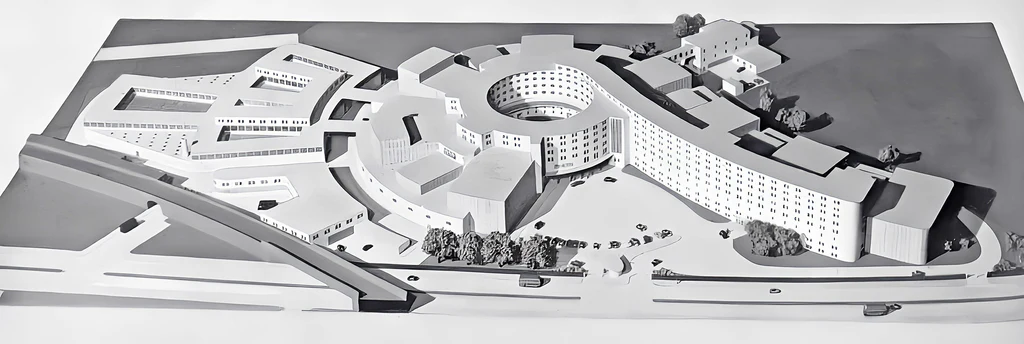

A few months later the BBC announced their own plans to buy the land for a new television centre. They got into a heated battle with the council stating that “hundreds of people could now lose the chance to have their own home”. Two years later, the dispute was settled with the BBC getting 13 acres and the council getting 8 acres. The remaining 7 acres, which included the site of the old Japanese Garden, was designated as a public open space to be known as Hammersmith Park. This opened in 1955.

Around the same time the BBC acquired the nearby Lime Grove studios which had been closed by Rank in 1948 with the loss of 550 jobs.

Throughout all this time the White City stadium remained relatively unaffected, and was still being used as the 1980s dawned. It was considered the home of London greyhound racing and also hosted various other popular sporting events including boxing, football, rugby and speedway. It was also used for music concerts, religious gatherings, stock car racing, american football and even cheetah racing! Its resident female tabby cat became famous for killing 12,000 rats over a 6-year period.

In 1984, in a shock move, the 76-year old stadium was sold to developers for 1.7 million who announced plans to demolish it. They gave notice to the Greyhound Racing Associating to quit by the 1st October. 300 full and part-time staff lost their jobs. By March 1985 the demolition was complete.

In June 1985 it was announced that the BBC had bought the site for 30 million and planned to build a new radio headquarters and move all their staff out from central London. The first new building was completed in 1990 but the original plans had since been abandoned and the new building simply became extra office space. Phase 2 wasn’t completed until 2004 with the addition of more offices to create a ‘Media Village’. The BBC sold the site in 2015 and nowadays it’s known as White City Place.

The Japanese Garden can still be seen in Hammersmith Park, although much altered and rebuilt over the years.

The Flip-Flap & Mountain Railway

The Flip Flap was a showpiece for the 1908 Franco-British Exhibition in much the same way that the Eiffel Tower was the center of the Paris World’s Fair in 1889. The Flip Flap had two arms that were 150 feet long with a carriage attached to each end, each with a capacity of 40 people. It took three minutes and 20 seconds for the journey from one side to the other and cost sixpence. It carried over a million people in 1908. It was fabricated by the Cleveland Bridge and Engineering Company of Darlington.

At the 1909 exhibition, a baby was born at the Kalmuck Camp which was located within the exhibition grounds. The tribe had a tradition of naming a child after the first thing the mother sees after giving birth. The baby was named Flip Flap.

A Scenic Railway roller coaster was built for the 1908 exhibition by John Henry Iles who had recently acquired the UK rights from LaMarcus Thompson. He operated it as a concession and later boasted that he recouped the construction costs in just 6 weeks. The site owners wanted a piece of the action, so the following year they built their own ‘scenic railway’ known as the Mountain Railway. They designed the whole thing themselves, and one man was killed during construction. The council later issued a summons stating that “the stability of the structure was not up to standard.” Expensive repairs were needed before it opened to the public.

During that first season, three separate accidents occurred – two involved collisions between trains and the third involved a train derailing, Around 30 people were injured in total. A newspaper columnist said the ride should be closed without delay “This thing is obviously catastrophic. Whatever else the White City is run for, it certainly should not be run to enrich the undertaker”.

The ride reopened the following year with “new safety features” and operated for the 1909, 1910 and 1911 exhibitions. For 1912 the ride was dismantled and moved to a new location as the site owners wanted all the amusements grouped together in an area they called Merryland. For the 1914 exhibition it was supposedly demolished and replaced by a new version “the biggest in the world” themed around the Grand Canyon.

Leave a Reply